Casino Royale (1953): The birth of a style

Continued from The Birth of a Hero discussed here.

So with a better understanding of the James Bond literary character as found in the first novel, let us take a brief overview of the storytelling style adopted for the book and series at large, notwithstanding a few exceptions.

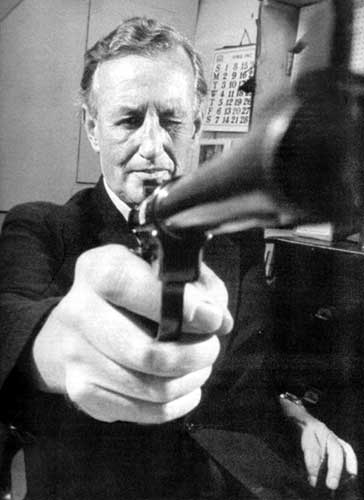

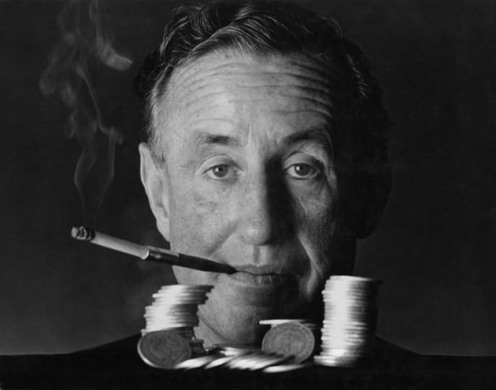

Ian Fleming, as described by friends and biographers, put a lot of himself in the 007 adventures. Many authors follow this same pattern. They discover inspiration in what they know, what they like and dislike and find interesting, and Fleming was no exception. He was born into a rather well off family, was educated at fine academic institutions, was healthy and quite athletic during his youth, was director of the Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, and took advantage of the great many little pleasures in life whether they were healthy or not. Needless to say that many of these personal details were lent to the character of Bond in some fashion or another in the books. There are some other crucial facts about Fleming and his life that determined how the stories were written, namely his profession, his privilege of having travelling a lot and finally his nationality.

Being a journalist by trade, Fleming had a brilliant knowledge of the English language and a fine eye for detail. His style is always very colourful, his descriptions are detailed and precise, but never mundane. He consistently succeeds in finding clever, humorous, fresh and apt words in order to bring his characters and locations to life. If you can’t picture in your head the look, shape and aura of a character or place after reading one of his descriptions, you probably just need to brush up on your English. What should be glamorous comes off as such, what should be drab comes off as such, and those who should come off as nefarious and hideous most certainly come off as such. Like many Bond fans today, I had seen all the of films multiple times before even thinking of adventuring myself into the books. I essentially did so to learn about the source material without, but I admittedly did not expect very much in terms of quality writing. I’m not sure why that was exactly, although I assume that disappointing film entries like Diamonds are Forever, The Man With the Golden Gun and Moonraker were partly to blame. After all, how good can the source material for rubbish like that be? Imagine my surprise upon discovering not only Ian Fleming’s imaginative stories, but also a rich, vivid and textured vocabulary that adds so much quality and respect to the books. If a reader truly feels that the stories themselves to be boring, there is little one can do to convince otherwise. I think, however, that one would be hard pressed to thrash the flare, wit and inventiveness with which the author presents his stories.

Cayeux-Sur-Mer, France. The real Royale-Les-Eaux?

Fleming also travelled very much in his lifetime, whether as a student, as an agent of Naval Intelligence, as a journalist or while on holiday. Russia, France, Austria, Canada, Jamaica, the United States, Ian Fleming, while always maintaining his Englishness, was quite the man of the world. He did take pleasure in discovering and learning about different places and their cultures. Obviously, England and its way of life came first and at times the books demonstrate some layers of snobbishness and even slight racism (not copious amount mind you. In fact, one of the characters in Live and Let Die even corrects Bond when the secret agent says the word ‘nigger’), but he recognized in many ways the beauty, history and value of the many regions of the globe. This clearly carries over into his writing and is immediately discernable in the very first novel, Casino Royale. None of the action transpires in London, save for one pseudo-flashback scene in which M reads MI6’s file on Le Chiffre, le SMERSH agent Bond is tasked with cleaning out at the baccarat table. Everything occurs in and around a small coastal town in Southern France (fictional), Royale-Les-Eaux. Fleming devotes time from the story to provide the history and culture of this town, which apparently earned its fame and fortune through the carbonated water business. Casino Royale is but the first the of many novels in which Fleming sends his secret agent to very specific (non-fictional) and lively parts of the world. The stories therefore function like a travelogue of all the countries Fleming visited in his lifetime, whether before having created the character of Bond or in order to specifically perform some research for the novels.

Finally, there is Fleming’s English identity. England, like all the great or once great world powers, has its share of historical enemies and contemporary rivals. Wartime efforts often lead into obvious attempts at propaganda, conjuring up intentionally vicious, exaggerated and one-sided descriptions and accusations about the opposing side. In the early to mid fifties, England dealt with one definite enemy, communism in the shape of the Soviet Union, and was still haunted by the recently defeated Third Reich and Nazism. They were also dealing with numerous colonial losses, although that hurt English pride more than it did make enemies out of their former colonies. This chapter of the 20th century may not have witnessed active combat between the British and the Soviets, but their many unfortunate countries that stood in the middle of this ideological wrestling match were victims of proxy warfare, not to mention that the British and Soviet government certainly did not trust one another. Given that James Bond is a loyal servant of Her Majesty, this element of rivalry becomes a crucial element in what kind of picture of the enemy Fleming chooses to paint. In fact, it works a lot like the propaganda factor I mentioned briefly earlier. There isn’t anything subtle about the elaborate resumes and descriptions Fleming concocts for his protagonist’s enemies. The more sinister, the uglier, the stranger, and the more socially inept they are, the better. Some of them are cursed with physical traits which make them appear strange and hideous, or even animalistic at times. In this black and white world, there is a never ending battle between good and evil, with Bond at the forefront of the side for good, foiling the nefarious plots conjured up by England’s enemies. None of the SMERSH operatives encountered in the early are blessed with redeeming qualities, save one: their intelligence in constructing such sophisticated and complex plans. Many of Bond’s foes are brilliant madmen, vastly more educated and possessing overwhelmingly greater cognitive skills than most common people. And yet, their talents are used for evil deeds, be it smuggling, terrorism or even gambling in the case of Le Chiffre. One could argue that Fleming is throwing a proverbial bone to England’s enemies. ‘You’re smart and force us to remain alert, but we shall defeat you anyways.’ Given the nature of the stories and the time when they were written, it is unsurprising that Bond almost never comes across foes who are English, or even from the United Kingdom at large. Heaven forbid.

It probably goes without saying that there were other factors at play which dictated why Fleming wrote these novels the way he did. I believe that is background as a journalist, his travels to disparate countries around the world and his nationality, as well as his nation’s place in the world at the time, are some of the more influential elements. They shaped not only the nature of the stories but equally his prose. Just like many other authors, Fleming used what he knew and believed in, only his version was always shaken, not merely stirred.